Official website of Abrar Ahmed Shahi | Free delivery for order over Rs 999/-

Ibn al-Arabi’s works in manuscripts and its Global Distribution 2025

Blog post description.

IBN AL-ARABI MANUSCRIPTSIBN AL-ARABI BOOKS

Abrar Ahmed Shahi

4/6/202510 min read

1. Introduction: The Enduring Legacy of Ibn al-Arabi and the Importance of His Manuscript Tradition.

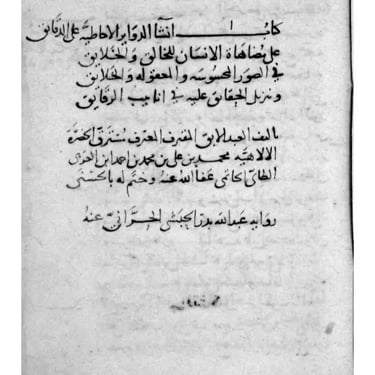

Muhyiddin Ibn al-Arabi (1165-1240 CE), revered as "Shaykh al-Akbar" (the Greatest Master), stands as a towering figure in the history of Islamic thought.1 His profound contributions, particularly to the esoteric and mystical dimensions of Islam, have resonated across centuries, shaping the intellectual and spiritual landscape of the Muslim world.3 Central to his enduring influence is his concept of wahdat al-wujud (Unity of Being), a doctrine that posits the fundamental oneness of existence and the manifestation of the Divine in all things.4 Understanding the intricacies of Ibn al-Arabi's thought necessitates a deep engagement with his extensive literary output, which was primarily disseminated in manuscript form during his lifetime and for centuries thereafter.6

In an era preceding the advent of printing in the Islamic world, manuscripts served as the primary vehicles for the transmission of knowledge.6 These handwritten texts are indispensable for scholars seeking to authenticate Ibn al-Arabi's vast corpus and trace the historical trajectory of his ideas.7 Unlike printed editions, which often rely on later copies and may contain editorial interventions or inaccuracies, manuscripts offer a more direct connection to the original context of their creation.5 The meticulous study of these primary sources allows for a deeper and more nuanced comprehension of Ibn al-Arabi's complex teachings.

The contemporary landscape of Islamic manuscript studies has been significantly enhanced by the emergence of online archives, providing unprecedented access to information and resources for scholars worldwide. Notably, the Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi Society (MIAS) archive 7 and the Ibn al-Arabi Foundation 15 serve as crucial digital repositories, offering catalogs, databases, and sometimes even digitized copies of Ibn al-Arabi's works. These platforms play a vital role in facilitating research by overcoming geographical barriers and enabling scholars to engage with manuscript traditions from diverse locations. This introductory report aims to provide an overview of the extensive manuscript tradition associated with Ibn al-Arabi's works. It will delve into the historical methods of their copying and preservation, map their global distribution across major libraries and collections, identify his five most important works based on scholarly recognition, and detail some of their most significant manuscript copies, including their current locations and estimated dates. Finally, a summary table will encapsulate key findings, offering a valuable resource for those embarking on the study of this seminal Islamic thinker.

2. The Art and Science of Transmission: Manuscript Copying in the Islamic World.

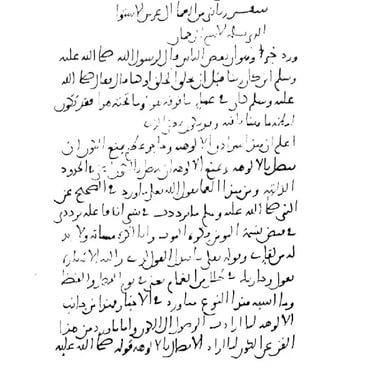

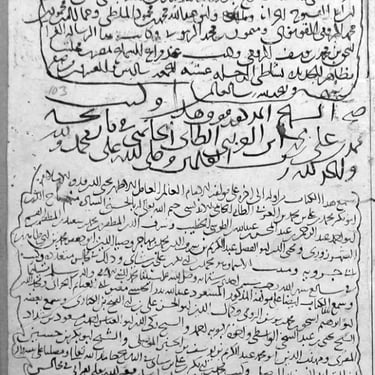

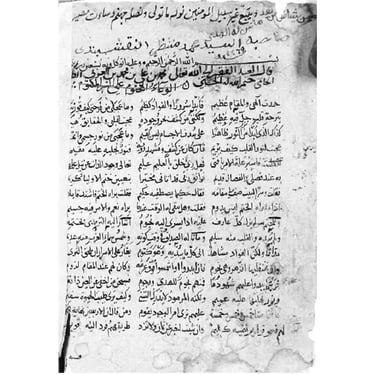

The dissemination of Ibn al-Arabi's prolific writings throughout the Islamic world relied heavily on the intricate processes of manuscript copying, particularly during the 12th and 13th centuries.8 At the heart of this endeavor were professional scribes, known as warraqun, who underwent rigorous training in calligraphy and were expected to adhere to high standards of accuracy in their transcriptions.8 Calligraphy was not merely a means of recording text but was considered a highly esteemed art form in the Islamic world, especially when applied to religious texts.8

A notable practice that facilitated the rapid multiplication of texts was the dictation of works by authors to multiple scribes simultaneously.11 This method allowed for the efficient production of numerous authorized copies from a single reading, significantly accelerating the circulation of knowledge. Furthermore, the process of sama' (oral transmission and verification) played a crucial role in ensuring the authenticity and accuracy of manuscripts.9 In sama' sessions, works were read aloud, either by the author or by a trusted reader, in the presence of the author, who would then certify the correctness of the copy. This emphasis on oral transmission, deeply rooted in the scholarly culture of the time, provided a vital layer of quality control and maintained a strong connection to the author's original work.11

The production and dissemination of manuscripts were closely intertwined with the activities of scholarly and religious circles.7 Mosques served not only as places of worship but also as centers for learning and the recitation of texts. Madaris (educational institutions) and Sufi khanqahs (lodges) also played a pivotal role in fostering intellectual exchange and facilitating the copying of manuscripts.7 Libraries, often attached to these institutions, were essential for housing manuscript collections and providing resources for those involved in the labor-intensive process of copying.7 The support and patronage extended by rulers and wealthy individuals further contributed to the flourishing of manuscript production, enabling the creation of elaborate and high-quality copies.8

The introduction of paper around the 8th century CE marked a transformative shift in manuscript culture within the Islamic world.8 Compared to earlier writing materials like parchment (vellum), paper was more readily available, easier to manufacture, and significantly more affordable.11 Its properties, such as its ability to absorb ink well and its resistance to cracking, made it an ideal medium for extensive writing and record-keeping.11 The increased availability of paper spurred the development and refinement of various calligraphic styles, each with its own aesthetic characteristics and functional suitability for different types of texts.8 Styles such as Kufic, Naskh, Thuluth, Ta'liq, and Nasta'liq emerged and evolved, contributing to the rich visual heritage of Islamic manuscripts.

3. Safeguarding Knowledge: Historical Methods of Manuscript Preservation.

The preservation of Ibn al-Arabi's manuscripts across centuries involved a range of techniques and practices within the Islamic world.10 A significant mechanism for ensuring the long-term upkeep of libraries and their manuscript holdings was the establishment of endowments (waqf).7 These charitable trusts provided financial support for the maintenance of collections, the training of staff, and sometimes even the production of new copies, demonstrating a societal commitment to the preservation of knowledge.

Libraries, often located within religious or educational complexes, implemented environmental controls to protect their valuable manuscripts, although these methods may not have been as sophisticated as modern climate control systems.20 Efforts were made to shield manuscripts from excessive sunlight, moisture, and dust, which could cause significant damage over time. Traditional methods of pest control also played a role in safeguarding manuscripts from biological threats.20 Natural repellents derived from herbs and spices, such as turmeric, neem leaves, and black cumin, were employed to deter insects and other pests that could infest and destroy manuscript materials.

When manuscripts did suffer damage due to age, use, or environmental factors, various repair and restoration techniques were employed.20 Skilled artisans specialized in bookbinding, ensuring that the physical structure of the codex was sound and protected the individual leaves. Tears and other damage to paper or parchment were also addressed through careful repair methods, often using materials and techniques that were sympathetic to the original construction of the manuscript.

Major libraries in prominent cities across the Islamic world, including Baghdad, Cairo, Damascus, and Konya, served as crucial repositories for vast collections of manuscripts, including the works of Ibn al-Arabi. Collections housed within mosque complexes, such as the renowned library of Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi in Konya, played a particularly important role in preserving the intellectual heritage of specific scholarly traditions.7 Over time, many of these collections were eventually transferred to state-run or university libraries, ensuring their continued safekeeping and accessibility for future generations of researchers.7 Despite these efforts, the preservation of historical manuscripts has always been a challenging endeavor, with natural decay, insect infestations, and adverse environmental conditions posing ongoing threats to these fragile documents.23

4. Mapping the Intellectual Landscape: Global Distribution of Ibn al-Arabi's Manuscripts.

The global distribution of Ibn al-Arabi's manuscripts reflects the wide geographical reach and lasting impact of his thought. The MIAS archive website provides valuable insights into the extent of this manuscript tradition.7 The MIAS Archive Project, initiated in 2002, has focused on compiling a comprehensive database of Ibn al-Arabi's works and collecting digital copies of significant historical manuscripts.7 To date, the archive holds over 1,500 manuscript copies attributed to Ibn al-Arabi and his intellectual circle.7 Furthermore, MIAS researchers have inspected and classified over 3,000 manuscripts, with a particular emphasis on collections in Turkey, Syria, and Egypt.7 For members undertaking academic research, MIAS offers access to a detailed searchable online database, and a concise version of their Archive Catalogue is also available in PDF format on their website.7

The Ibn al-Arabi Foundation website also sheds light on the manuscript sources crucial to their work.15 The Foundation is dedicated to producing critical Arabic editions of Ibn al-Arabi's writings, relying on the "best available manuscripts" for their editorial process.15 They have specifically mentioned utilizing collections such as the Fakhr ud-din collection and the kutubkhana Asfia collection in their endeavors.15 Recognizing the importance of accessibility, the Foundation has also taken steps to digitize and make some of these manuscript resources available online.15

General online searches corroborate the concentration of Ibn al-Arabi's manuscripts in several key geographical areas and libraries. Turkey, particularly the cities of Istanbul and Konya, emerges as a major repository. This is likely due to the historical presence of Ibn al-Arabi's intellectual successors in Anatolia and the long tradition of manuscript preservation within Ottoman libraries. Significant holdings are also found in major libraries such as the British Library in London 30, the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford 17, and Leiden University Libraries in the Netherlands.6 Beyond these major centers, manuscripts of Ibn al-Arabi's works can also be found in libraries and private collections in Syria, Egypt, India (particularly the State Central Library in Hyderabad), Yemen, and across various European and North American institutions.7

5. Identifying the Cornerstones: The Five Most Important Works of Ibn al-Arabi.

Based on their frequent appearance in scholarly literature, their profound influence on subsequent Islamic thought, and their central significance within the Akbarian tradition, the following five works stand out as the most important contributions of Ibn al-Arabi:

Al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya (The Meccan Revelations): This monumental, encyclopedic work is Ibn al-Arabi's magnum opus, comprising an astonishingly vast exploration of Sufi metaphysics, cosmology, spiritual anthropology, psychology, and jurisprudence.1 Its 560 chapters delve into the inner meanings of Islamic rituals, the stations of spiritual travelers, the nature of cosmic hierarchy, and the spiritual significance of the Arabic alphabet, among a multitude of other topics.

Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam (The Bezels of Wisdom): Often considered the quintessence of Ibn al-Arabi's spiritual teachings, this relatively concise work comprises twenty-seven chapters, each dedicated to the spiritual meaning and wisdom embodied by a particular prophet. It has been the subject of numerous commentaries and remains one of his most influential works.

Tarjumān al-ashwāq (The Interpreter of Desires): This collection of love poetry, inspired by Ibn al-Arabi's encounter with a woman named Nizam in Mecca, is accompanied by the author's own mystical commentary, which interprets the poems as expressions of spiritual longing and divine love.1 It was one of the first of his works to be translated into a Western language, highlighting its early recognition.

Rūḥ al-quds (The Holy Spirit): This treatise offers insights into Ibn al-Arabi's spiritual experiences and includes biographical sketches of over fifty Sufi masters he encountered in Andalusia.1 It also contains a critique of contemporary Sufi practices, making it a valuable source for understanding the social and religious context of his time.

ʻAnqāʼ Mughrib fī Maʻrifat Khatm al-Awliyāʼ wa Shams al-Maghrib (The Fabulous Gryphon Regarding the Seal of Saints and the Sun of the West): This work delves into the complex concept of sainthood in Islamic mysticism, focusing on the figure of the Seal of the Saints (khatm al-awliya') and its connection to the Mahdi.1 It is considered an important early exposition of Ibn al-Arabi's doctrine of walaya (spiritual authority).

6. Tracing the Earliest Witnesses: Significant Manuscript Copies of Key Works.

The preservation of Ibn al-Arabi's intellectual legacy is deeply intertwined with the survival and study of his manuscripts. For each of the five most important works identified, several significant manuscript copies offer invaluable insights into the transmission and reception of his ideas.

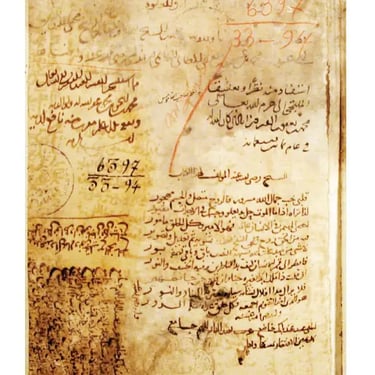

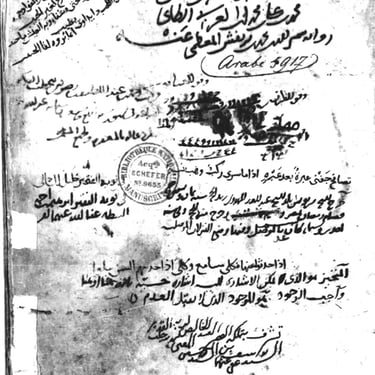

Al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya: The Konya Manuscript 114, housed in the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istanbul, is an autograph manuscript of the second recension, completed in 636 AH/1238 CE. Beyazit 3750 1 at the Beyazit State Library in Istanbul contains a significant portion, Chapter 560, copied in 947 AH/1540 CE from Ibn al-Arabi's original. Readings of the Futūḥāt dating back to 601-603 AH/1204-1206 CE are recorded in a manuscript held under the shelfmark University 79.151 Ahmed 5109 151 contains a copy of Tanazzulat composed in Mosul in 601 AH/1204 CE, often considered part of the broader Futūḥāt. Esad Ef. 2694 1 at the Süleymaniye Library in Istanbul bears a note indicating the successive stages of the work's composition.

Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam: The earliest extant manuscript is Evkaf Müzesi 1933 152 at the Türk ve İslam Eserleri Müzesi in Istanbul, transcribed by Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi and authenticated by Ibn al-Arabi himself in 630 AH/1232-1233 CE. Yusuf Agha 7838 (or 5624) 27 in the Konya Yusuf Agha Library contains a copy written by al-Qunawi and approved by Ibn al-Arabi, with a hearing certificate from 627 AH/1230 CE. Beyazid 3750 27 at the Beyazit State Library in Istanbul appears to have been copied in Aleppo in 682 AH/1283 CE. Asafia Library 140 27 at the State Central Library in Hyderabad dates to 689 AH/1290 CE but was reproduced from an original by Ibn al-Arabi from 632 AH/1234-1235 CE. Veliyuddin 51 151 at the Beyazit State Library houses a collection of 17 works, with notes indicating they were copied from Ibn al-Arabi's own hand.

Tarjumān al-ashwāq: R.A. Nicholson's critical edition relied on three ancient manuscripts 126, the precise locations of which would require further investigation into his scholarly papers. A copy held at the Paris Bibliothèque Nationale (MS 2348) 1 dates to 1094 AH/1683 CE. Given the Süleymaniye Library's extensive holdings, it likely contains significant copies, as does the British Library and the Bodleian Library within their large Islamic manuscript collections.17

Rūḥ al-quds: A copy held under the shelfmark University 79 151 contains readings dated 601-603 AH/1204-1206 CE. A copy from 618 AH/1221 CE is noted as having been in Konya.137 Given MIAS's research focus, significant copies likely reside in major libraries in Turkey, Syria, and Egypt.7 The Ibn al-Arabi Foundation utilizes manuscripts for their critical editions.139 The British Library and Bodleian Library also likely hold copies within their extensive collections.

ʻAnqāʼ Mughrib fī Maʻrifat Khatm al-Awliyāʼ wa Shams al-Maghrib: MS Berlin 3266 145 at the Berlin State Library, transcribed in Fez in 597 AH/1201 CE, is considered a very early and possibly the oldest extant manuscript of this work. As with other key texts, copies are likely held in major libraries in Turkey, Syria, and Egypt.7 The Ibn al-Arabi Foundation has published a critical edition 147, indicating their access to significant manuscript sources. The Süleymaniye Library and Bodleian Library are also potential locations for manuscript copies.

7. Conclusion: Appreciating the Rich Manuscript Heritage of Ibn al-Arabi for Contemporary Scholarship.

The manuscript tradition of Shaykh al-Akbar Ibn al-Arabi's works is vast and globally distributed, encompassing thousands of copies preserved in libraries and archives across the world. These handwritten witnesses to his profound intellectual and spiritual legacy serve as indispensable primary sources for understanding the intricacies and nuances of his thought, offering a more direct and potentially more accurate representation than later printed editions. The ongoing efforts of dedicated institutions such as the MIAS archive and the Ibn al-Arabi Foundation are crucial in cataloging, digitizing, and making these invaluable resources increasingly accessible to researchers and scholars worldwide. Continued engagement with these manuscripts remains vital for advancing our comprehension of Ibn al-Arabi's enduring influence on Islamic thought and the multifaceted traditions of Sufism.

8. Appendix: Table of the Five Most Important Works and Their Top Five Manuscripts.

Works Cited:

“Al-Futuhat Al-Makkiyya.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

“Al-Futuhat Al-Makkiyah: The Openings in Makkah – Volume 1.” IBT Books.

“Ibn Al-Arabi [Biography].” Ibn Al-Arabi Foundation.

“Ibn Al-Arabi’s Kitāb Fuṣūṣ Al-Ḥikam Wa-Khuṣūṣ Al-Kalim.” Brill.

“Ibn Arabi.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

“Illuminated Manuscript.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

“Islamic Golden Age.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

“Islamic Manuscripts.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

“Manuscripts and Their Importance in Islamic Cultural and Religious Studies.” Maydan.

“Manuscripts: Preservation in the Digital Age.” UNL Digital Commons.

“Preserving Manuscript Works in the Original or by Reformatting?” Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation.

“Rūḥ.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

“Selections from Ibn Arabi’s Tarjuman Al-Ashwaq (Translation of Desires).” Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi Society.

“Tarjumān Al-Ashwāq.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

“Tarjuman Al-Ashwaq: A Collection of Mystical Odes.” Exotic India Art.

“The Astounding Role of Islamic Scholars in Saving the Ancient World’s Greatest Knowledge.” History Skills.

“The Islamic Golden Age.” Lumen Learning.

Explore

abrarshahi@yahoo.com

Discover

Connect with our collection

+92 334 5463996

Chaklala, Rawalpindi